FAQs on Indian Agriculture Investments in Ethiopia

Why has the recent surge of foreign land acquisitions and leases been dubbed a “global land grab”?

Since the food price crisis of 2007, there has been a rapid increase of foreign acquisition of land in developing countries by foreign governments, private agro- enterprises and private equity funds for commercial farming ventures. In 2009 alone, foreign investors acquired 60 million hectares (ha) of land – the size of France – through purchases or leases of land for commercial farming. Before 2008, the expansion of global agricultural land was less than 4 million ha annually. Nearly 75 percent of the deals are taking place in sub-Saharan African countries that have high rates of food insecurity and agricultural systems, especially small-scale farming and pastoralism, adversely impacted by decades of neglect by governments. Most of the large-scale land deals are negotiated without the Free Prior and Informed Consent of the indigenous populations living on the land. In the worst cases, people are forcibly evicted from their land with little or no compensation. In addition to farms, the land acquired by investors includes grazing land, forest, and water sources, which are all essential for the livelihoods of millions of rural people.

Which sub-Saharan African countries are attracting the most interest?

Many African countries are attracting investor interest and witnessing large-scale land grabs. Ethiopia, Liberia, Mozambique, Sierra Leone, South Sudan, Tanzania, Zambia, Uganda, Nigeria, and the Democratic Republic of Congo are among those attracting the most foreign interest. Ethiopia is one of the preferred destinations for agricultural investments in Africa. Between 2008 and 2011, 3,619,509 ha were transferred to domestic investors, state-owned enterprises, and foreign companies, including Indian agro-enterprises.

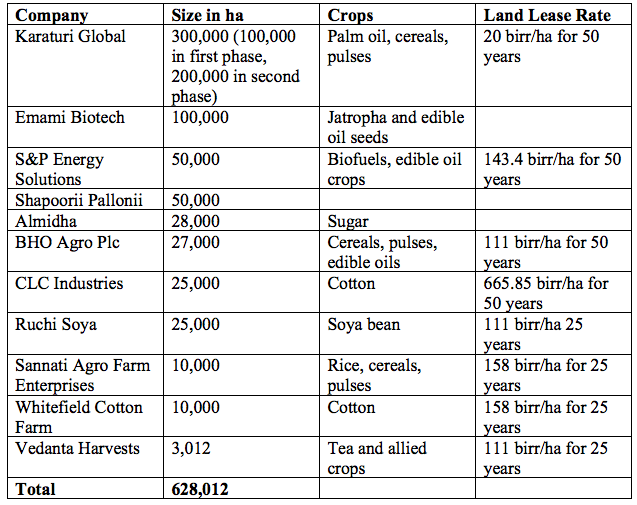

What makes land deals in Sub-Saharan African countries attractive is the supposed availability of fertile land, forests and water resources as well as the mouthwatering conditions offered by many governments in terms of cheap land leases over long-term periods, fiscal exemptions, and other incentives allowing a maximization of the profit that foreign companies can make out of their investment. India’s largest investor in Ethiopia, Karuturi, is acquiring land at a rate as low as 20 birr (Rs. 59/$1.10) per hectare. A host of other investors with significant land claims have acquired land at rates between 111 to 158 birr (Rs. 324/$6.05 to Rs. 461/$8.62)

Why are nation-states and private foreign enterprises investing so heavily in sub-Saharan African land?

The global land rush is the reaction of investor countries to the food price crisis of 2007, which was partly brought on by increased speculation in food commodities and a decline in the growth rate of world agricultural production, a result of several factors, including lack of investment in agriculture, climate change, and crops and cropland being diverted to biofuels.

In response to immediate concerns wrought by the recent financial crisis, wealthy private investors have also directed investments into offshore farmland as a way to increase profits in newly carved out biofuels and soft commodities markets.

Where in Ethiopia are investments taking place? Where are Indian firms concentrated?

The larger share of investments is taking place in five administrative regions in Ethiopia – Afar and Amhara in the North, Oromia in Central Ethiopia, and Gambella and the Southern Nations, Nationalities and Peoples Regions (SNNPR) in the South.

Indian enterprises are largely concentrated in Gambella and Afar. Karaturi Global is the largest investor in Gambella with plans to farm palm oil, cereals, and pulses on 300,000 ha of land in the region. Indian investments generally take place in regions where the government offers extra tax incentives. Incidentally, these are regions that are targeted by the villagization program.

Only a few direct Indian investments have been identified in Lower Omo, where 445,000 ha have been taken away since 2008 from local populations to grow mainly sugar and cotton. The region is primarily developed by state-owned companies for the production of sugar but India is playing a key role in this region through the Export-Import (EXIM) bank of India (see below).

Is India implicated in providing support to private Indian investments?

While the Indian government does not currently offer direct financial support to firms to invest abroad, EXIM bank, a government financial institution, has opened a $640 million line of credit to the Ethiopian government to expand the country’s sugar sector. The credit line commits Ethiopia to import 75 percent of the goods and services, such as consultancy services, from India.

Some Indian entrepreneurs, like Rana Kapoor, CEO of YES bank and a member of the Government of India’s Board of Trade, as well as the Federation of Indian Chambers of Commerce and Industry (FICCI) have championed the overall investment activity.

How much land has been acquired by the Indian enterprises in Ethiopia? What crops do they plan to grow?

Indian firms have acquired over 600,000 ha of land. Most investors plan to grow edible oils and crops while a few have plans to grow cotton.

What is the current situation of food security in Ethiopia? How are the investments likely to impact Ethiopia's food security?

Ethiopia currently suffers endemic poverty and food insecurity. It is the fifth “hungriest” nation in the world, according to IFPRI’s 2012 Global Hunger Index. Whereas 80 percent of the population is engaged in agriculture, over 8 million Ethiopians (over 10 percent of the population) are deemed chronically hungry. Every single year, 10 to 15 million people – over 15 percent of the population – depend on food aid for their survival.

In this context, the Ethiopian government argues that foreign investment in agriculture will bring economic development and eventually reduce hunger and poverty. The government claims that investments are necessary to modernize agriculture, bring new technologies, and create employment.

However, investigations by the Oakland Institute (OI) and other NGOs show that large-scale plantations create little employment and bring limited benefits for the local populations. On the contrary, taking over land and natural resources from rural Ethiopians, is resulting in a massive destruction of livelihoods and making millions of locals dependent on food handouts. Furthermore, the low rental fees and the generous incentives provided to investors raise serious questions about the returns in terms of public revenue from these investments.

Do these investments involve human rights violations?

The US Department of State’s 2011 human rights report noted that the Ethiopian regime is responsible for massive human rights violations including arrests of hundreds of opposition members, activists, journalists, and bloggers. Other human rights violations identified include torture, beating, abuse, and mistreatment of detainees by security forces; harsh and at times life-threatening prison conditions; arbitrary arrest and detention; restrictions on freedom of assembly, association, and movement; police, administrative, and judicial corruption.

Land acquisitions are one area of widespread human right violations in Ethiopia. In its aggressive pursuit of agricultural investment, and through its so-called villagization program, the Ethiopian government has forcibly displaced hundreds of thousands of indigenous people from their lands, and has arbitrarily arrested and beaten individuals who have refused to comply with its policies. Rapes and killings involving security forces have also been reported in Lower Omo and Gambella regions. In the process of villagization, the government has destroyed livelihoods, and has rendered small-scale farmers and pastoralist communities dependent on food aid and fearful of their own survival.

Through the villagization program, the Ethiopian government plans to relocate 1.5 million people by 2013 in the country’s Gambella, Afar, Somali, Lower Omo, and Benishangul-Gumuz regions. Officially, the program’s objective is to provide people with access to new farmland, schools, health facilities, and basic infrastructure. The reality shows that the regions targeted for villagization are also those where the government is trying to bring in investors for large-scale commercial plantations.

Against all evidence, the Ethiopian government insists consultations are being held with host communities in all instances where land deals are occurring, no farmers are being displaced, and the land being granted is unused. OI field investigations, however, found that consultations with local indigenous communities did not occur, in violation of their right to Free and Prior Informed Consent.

Although Ethiopian officials claim that villagization is a voluntary program, OI investigations reveal that the government has forcibly resettled indigenous communities from land earmarked for commercial agricultural development, rendering them food insecure and fearful for their survival.

The Ethiopian government’s actions around villagization, forced displacement, and land acquisition are in clear violation of international law: the government has failed to show proof that alternative policies have been properly considered, failed to secure Free Prior and Informed Consent from displaced indigenous communities, failed to provide affected groups with mechanisms for redress, and failed to provide anything approximating fair compensation.

Do Indian investors and foreign states have any responsibilities with regard to the displacements?

Investors such as Karuturi reject any responsibility as regards the villagization program and related human right violations. Yet, support has recently emerged for the “Protect, Respect, Remedy” framework, which would require corporations and other business enterprises to avoid infringing on human rights and address the negative human rights impacts of their operations. In 2011, the U.N. Human Rights Council endorsed the “Guiding Principles for Business and Human Rights," which outline: “1) the duty of the State to protect against human rights abuses by third parties, including business enterprises; 2) the responsibility of a corporation to respect human rights…; and 3) the need for greater access to both judicial and non-judicial remedies for human rights abuses by business entities.” In fulfilling their responsibility to respect human rights, the Guiding Principles state that transnational corporations and other business enterprises should “avoid infringing on the human rights of others and should address adverse human rights impacts with which they are involved.” Second, corporations should also “[s]eek to prevent or mitigate adverse human rights impacts that are directly linked to their operations, products or services by their business relationships, even if they have not contributed to those impacts.” Third, corporations must exercise due diligence to “become aware of, prevent and address adverse human rights impacts.”

Foreign states that encourage and facilitate agricultural investments in Ethiopia also have extraterritorial human rights obligations vis-à-vis the Ethiopian populace. The Maastricht Principles – which were adopted in September 2011 by a group of experts in international law – “aim to clarify the content of extraterritorial State obligations to realize economic, social and cultural rights with a view to advancing and giving full effect to the object of the Charter of the United Nations and international human rights.” The Principles clarify that at minimum governments have an obligation to avoid causing harm in foreign countries, and should assess “the potential extraterritorial impacts of their laws, policies and practices on the enjoyment of economic, social and cultural rights.”

The dire situation of many indigenous communities in Ethiopia under the ongoing villagization program raises serious concerns under international law, implicating the obligations of Ethiopia, as well as those of the home governments of corporate investors with a hand in Ethiopian land deals.