Carbon Pipelines Fuel Environmental Racism ft. Sikowis Nobiss, Mahmud Fitil, Jaylen Cavil & Alejandro Murgia-Ortiz

For Land & Life

“Remember it is not just white landowners in rural Iowa who are concerned about these carbon pipelines, it is Black Iowans across the state, it is Indigenous Iowans across the state, it is migrant Iowans across the state, who are concerned about the harmful impacts that these pipelines will have because of environmental racism. The impacts of the decisions made here in this room affect Black, Brown and Indigenous Iowans the most and we are demanding you listen to us, listen to your mission to ensure that you have safety and environmentally responsible utilities for all Iowans. Do not just to continue to pad the pockets of those who have put you in the seats. We know there are conflicts of interest here and we are asking you to ignore those and please listen to your mission and please do what is right for all Iowans.”

Jaylen Cavil’s public comment to the Iowa Utilities Board

Andy Currier (AC): Hello and welcome back to For Land & Life — the Oakland Institute Podcast. My name is Andy Currier and I am your host for today’s episode where we will take a look at the environmental racism of a so-called “climate solution” here in the US. Summit Carbon Solutions intends to build the world’s largest carbon capture and storage pipeline across the Midwestern US, despite fierce and sustained citizen opposition. In November 2022, the Oakland Institute released The Great Carbon Boondoggle, unmasking the billion-dollar financial interests and high-level political ties driving the project forward despite opposition from a large and diverse coalition of Indigenous groups, farmers, and environmentalists rejecting the project as a false climate solution.

The project intends to build a 2,000-mile pipeline to carry CO2 across Iowa, Minnesota, Nebraska, South Dakota, and North Dakota, to eventually inject and store it underground in North Dakota. The promoters of the project fail to reckon with the growing body of evidence exposing carbon capture and storage (CCS) as a false climate solution. CCS projects have systematically overpromised and underdelivered. Despite billions of taxpayer dollars spent on these projects to date, the technology has failed to significantly reduce CO2 emissions, as it has “not been proven feasible or economic at scale.”

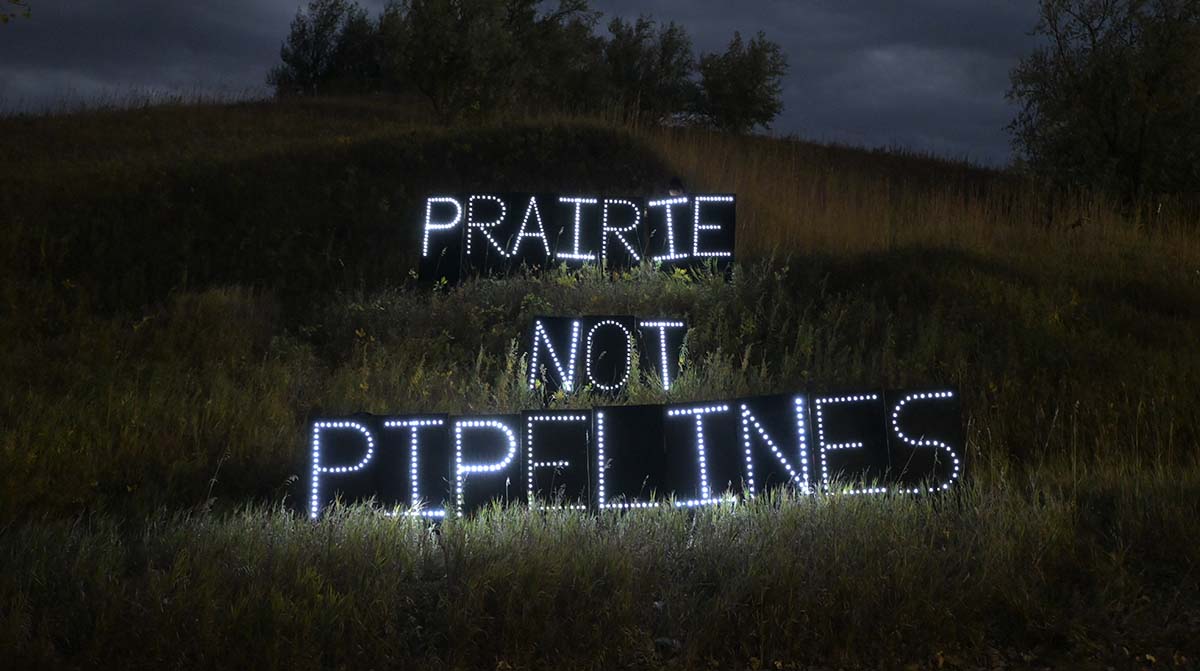

On January 17, 2023 a coalition of community organizations in Iowa mobilized to deliver the Oakland Institute’s expose to the IUB, Summit’s lawyer, and Governor Reynolds at the Iowa State Capital. The communities made their strong opposition to carbon pipelines clear and called for meaningful action. While media coverage so far has focused on the opposition white landowners in the path of the proposed route have to the pipelines — this project represents the latest instance of environmental racism as Indigenous, Black, Brown and Migrant communities will face some of the greatest risks if this project goes through.

Today, we are going to hear from several leading activists fighting against this and other proposed carbon pipelines in Iowa. First, we have Sikowis Christine Nobiss, Founder & Executive Director of Great Plains Action Society and Mahmud Fitil, Land Defense Director for Great Plains Action Society, a non-profit advocating for Indigenous communities throughout the Midwest.

Welcome Christine and Mahmud — let’s get right to it. What are the main concerns from Indigenous communities about Summit’s and other proposed carbon pipelines?

Mahmud Fitil (MF): There are a number of reasons, Andy. Thank you for inviting us and giving us a chance to speak here on the platform. A number of reasons the Indigenous communities are upset and concerned with these projects, particularly the bad taste left in their mouth after recent projects such as the 10 year-long odyssey of fighting KXL [Keystone XL Pipeline]. The Line 3 recent situation up in Minnesota, as well as right here in Iowa, the struggle against DAPL [Dakota Access Pipeline] that really ran roughshod over a lot of the people — both the majority of the population of Americans as well as the Indigenous communities — by not properly informing them and getting proper consent and not working with the communities to ensure proper health goals and safety were insured to those communities.

Same situation here, there's a big concern for transient workforce coming through with a lot of people from out of state that have no ties to the community. It's been documented through research that there's a grave risk to Indigenous women in particular, as well as children, boys, for human trafficking during these activities. Recently, during the Line 3 project up in Minnesota, there was a sex trafficking sting and several Enbridge employees were involved in that. Right here in Iowa, during a direct action on DAPL, we had a young Indigenous woman who was solicited by an employee who, as he was driving off the worksite, stated "how much for the little girl." You know, that's offensive for many reasons. But it's a long history of that going on in the United States, and it is just continually being perpetuated by the fossil fuel industry. Once we commodify the Earth, we begin commodifying people as well. So that's a big issue.

AC: Thank you, Mahmud. Christine, is there anything you'd like to add about the dangers that these “man camps” have for Indigenous communities?

“We have proven beyond a doubt that there is an increase in violence in our Indigenous communities, when man camps or temporary workforce housing units come through.”

Christine Nobiss (CN): We have proven beyond a doubt that there is an increase in violence in our Indigenous communities, when man camps or temporary workforce housing units come through. This doesn't just apply to pipelines, right? This applies to any type of large construction project that goes on in Indian country. So even if you're building massive roads or highways, or other types of extraction — mineral extraction, tree cutting, mining, or even hunting camps, sporting events — whenever you bring in large amounts of men into an area within Indian country, you often end up with increased sex trafficking, and increased rates of violence. Some of the stories are too horrid to even tell. It's really, really disturbing. And the thing is, it's not like these people, the older ones, the ones in their teens and 20s, aren't wanting to go there sometimes as well, they go there on their own sometimes because they're going to a party, they are promised a good time. And then that's where they get exploited and taken advantage of.

AC: And what are some of the other issues that Indigenous communities have with these projects?

MF: Primarily safety. These are much different than the traditional petroleum pipelines. They're known to be explosive, they have ductile fractures. There was an incident in Satartia, Mississippi. And zero communication has been given to the tribes. Many of the tribes such as the Omaha nation, and the Winnebago Tribe of Nebraska — their reservations live right along the path, literally as the pipe goes from Iowa, across Missouri into Nebraska. The pipe runs almost parallel to the border of the Winnebago reservation.

CN: Even cities like Des Moines, Sioux City, Waterloo, and Cedar Rapids don't have infrastructure that can deal with something like this, because you need specialized vehicles that can drive without oxygen. And then you need people to have masks and in oxygen tanks, to be able to be safe. So, when we talked to Michelle Free LaMere, for instance, who used to work in that realm on the Winnebago nation — I'm not sure if she was an EMT, or the police force — she said there's no way that the Winnebago nation is going to be prepared for something like this. If we can't even have large cities with massive budgets prepared for this, how are we going to have small towns and reservations prepared?

AC: That's really important to think about what happened in Mississippi, the explosion. If that happened in a more densely populated area, it'd be unimaginable what the consequences would be. To what extent has Summit meaningfully consulted tribes about this pipeline and gotten their consent and approval?

“These projects, both Summit and Navigator, traverse the Missouri River, skirting right along the edge of the Winnebago nation. During that meeting, we asked them on their own map to identify where the Winnebago nation of Nebraska was located and they had no idea.”

MF: I knew the Winnebago tribe was never really engaged in the same manner, neither were the Omaha tribe, the Santee, the Yankton, or any of the other tribes along the route and the tri-state area that we're working with here in South Dakota, Nebraska, and Iowa. Throughout the Great Plains, we saw that they were in a mad rush to put their information/propaganda sessions out to the public and spoon feed everybody all the benefits and why the projects need to be approved. We started reaching out to the Tribal Historic Preservation Officers (THPOs) of each of the tribal nations that find themselves along the Missouri River Valley, which subsequently is a major portion of the route as it traverses from Iowa into the greater Plains Region. We were able to secure, finally, an informational session and tribal meetings with Summit folks. They do actually have a tribal liaison (Erin Salisbury) who attended the meeting, but oddly enough, did not speak very much. They provided us a map, the Summit project map and it included the tribal nations, the sovereign nations along the route. However, they were just greyed-in areas, and they were not denoted by any type of name or anything like that. During that meeting, we asked a very simple question, because it seemed like the concerns of tribal members didn't really matter. They just tailored the same speech that they had been giving around Iowa to other communities, and threw in some things that they thought would be attractive to Native Americans, like "Hey, we're gonna have jobs available for you" — which we all know, from previous experiences, that when there's a build-up, there will be thousands of jobs, but those workers will be brought into state from other areas, so it's not going to benefit the local economy. In the end, it'll probably be a couple of dozen people that have jobs, if that. They always like to play the jobs numbers and use the unions out there. But the reality of it is, it's a lot more risk than it is any type of reward for the tribal communities. They felt very upset that they were last in line to be consulted as sovereign tribal nations. Treaty is the supreme law of the United States, and they do need to be consulted regarding projects that are in or on their historic tribal lands and cultural areas. These projects, both Summit and Navigator, traverse the Missouri River, skirting right along the edge of the Winnebago nation. During that meeting, we asked them on their own map to identify where the Winnebago nation of Nebraska was located and they had no idea. Between the five Summit representatives that were on the meeting, including their tribal liaison, they had no idea where the Winnebago Tribe of Nebraska reservation is, which is the closest reservation to the actual project.

AC: Wow, I think that's a very clear example. Despite Summit saying they've done all these consultations with Indigenous communities, the fact they couldn't even locate the Winnebago tribe on the map says a lot. With that in mind, Christine, do you think Summit actually cares about Indigenous communities?

CN: No, not if Bruce Rastetter is at the helm. I highly doubt he knows anything about Indigenous communities. Iowa was highly genocided and colonized because it's the only state that is bordered by the Missouri and Mississippi Rivers. It's absolutely beautiful farmland that you can cultivate. Indigenous folks were already doing that, they were already growing corn here and all sorts of things. But they were doing it in a sustainable way. And all of a sudden, settler invaders came in, and they're like, "Wow, amazing land, let's implement our colonial capitalist farming practices." So, natives were really cleared out of here. The institution of Iowa itself is built on white supremacy and still perpetuating it. To me, it wouldn't be surprising that Rastetter doesn't know anything. He's typical of many people. He's typical of any Iowan that was brought up, and given no information in school past 1800 about natives.

AC: We've talked a bit about the dangers of the pipeline itself, and the route of the pipeline. What about where the carbon is going to be stored? As our report points out, this has never been proven at scale. What are some concerns specifically around environmental racism about where they're going to store this carbon in North Dakota?

MF: The final area of sequestration for the carbon dioxide in North Dakota is centered directly between the northern border of Standing Rock Reservation and the southern border of Ft. Berthold Reservation. So, it continues along this legacy of this country engaging in environmental racism. If any of these ill effects were to actualize or become a problem for the local area, it would definitely affect Indigenous communities. And once again, they struggle with having limited resources and trying to manage their nation's affairs and being plagued with several issues living in rural environments, not having access to state of the art or top-notch health care often, and things like that. They want to have this thing built out within three years, which, as we mentioned, there won't be regulations prepared until three years. These are all big red flags for Indigenous nations. This is part of the reason why the Winnebago tribe engaged the IUB and tried to formally submit an environmental impact study, in part for the sequestration on the ground. It also has something to do with the Native Americans tied to the land, and that there's an entire ecological system living underground. What will happen if we start pumping thousands and thousands of metric tons of CO2 underground? We saw what happened with fracking and it was too late. When they started doing all these injection wells down in Oklahoma, Texas, and so on, it created a lot of seismic activity. This is really a largely unproven technology. They've never done it on the scales that they are proposing for both of these pipelines. And, once again, they're putting the burden or the risk on communities of color that are ill adapted, or ill prepared to fight in meaningful ways, because of lack of resources and a lot of other additional struggles going on in their communities.

“Another Indigenous perspective on the matter – we have a lot of creation stories that come from underneath the ground. Vine Deloria once said, our sacred sites don't just live on the land, they go to the center of the earth, and then out into the universe. They will be putting in a foreign agent, a toxic agent into the ground, and it's going to upset biomes that are exceedingly important to the functioning of our planet.”

CN: Another Indigenous perspective on the matter — we have a lot of creation stories that come from underneath the ground. Vine Deloria once said, our sacred sites don't just live on the land, they go to the center of the earth, and then out into the universe. They will be putting in a foreign agent, a toxic agent into the ground, and it's going to upset biomes that are exceedingly important to the functioning of our planet. They're injecting this gas back into the earth in a way that's not supposed to be in there. It just blows my mind that they want to construct this crazy contraption. You see what their plants look like, they're apocalyptic-looking. And then they want to attach more and more pipes, and upset more ground, and do this injection into the earth, where we really could just rematriate nine million acres of prairie in Iowa. I say nine million specifically, because there are nine million acres of prairie in Iowa that could be rematriated easily without even affecting farms. That's the amount of land that we call slopes and wetlands, where farmers will plant on a slope that's above nine percent, or up to a riverbank or in a wetland knowing that those crops aren't going to succeed. But they get insurance for it. If we were to just say no, you can't do that, and rematriate all those areas, that would be nine million acres of prairie that we can rematriate with roots that are eight to twelve feet deep, which also would solve a lot of other problems we're facing here in Iowa because we're the most biologically colonized state in the country. We have massive erosion going on. We only have 60 harvests left before the soil is gone. Because once you take those deep roots out, the soil has just been washing away. So why can't we just rematriate that. And not only that, but let's be honest, the majority of farming that's going on in Iowa is for corn and soy that's monocrop, GMO sprayed with pesticides, herbicides, fertilizers. It's ethanol for the corn and cattle feed, and we don't necessarily have to do that. We could actually rematriate a ton more of prairie if we decided to be more efficient with what we're doing, and stop making ethanol, stop saying it's this bridge fuel, because it's really not: it's become a “fuel” fuel. Just focus on renewables and we could actually rematriate probably another five to ten million acres. One healthy acre of prairie sequesters five tons of carbon.

AC: That's what jumps out to me. It has come out how carbon intensive ethanol production is, with all the land use changes you mentioned, and then instead of addressing that by rematriating prairie they're building this huge web of pipelines.

CN: It's colonial capitalism. It's how colonial capitalists think, they can't just leave land alone. That's not even on the table. That's such a foreign perspective to them, just to leave land alone.

AC: Those are clear and strong closing words. Thank you, Christine. Thanks as well to Mahmud for joining us and sharing some of your perspectives. We're now going to turn and speak with Jalen Cavil, an organizer and Advocacy Director for the Des Moines Black Liberation Movement. Jaylen, if you could just start by talking a bit about your organization.

Jaylen Cavil (JC): I'm an organizer with the Des Moines Black Liberation Movement and the Advocacy Director. I've been in that role since we started in 2020. In the beginning of the summer of 2020, our group was formed out of the uprisings following the murder of George Floyd. We began organizing protests here in Des Moines, advocating for racial justice, advocating for police and prison abolition, specifically advocating against the Des Moines Police Department and calling for their defunding. And we've been doing that work ever since. We're a racial justice and an abolitionist organization, made up of young Black organizers here in the city of Des Moines, we advocate for Black folks all around Iowa. Advocating for racial justice takes us in a lot of different spaces, and has us organizing for a lot of different issues, because we know that white supremacy and capitalism are so intertwined. And all of these issues are so connected with each other. We will talk about racial justice, it includes of course, police and prisons. It includes health care, it includes education, and includes our climate and our environment. Right. We definitely tried to be holistic organizing and really fighting for the liberation of all Black people.

AC: And because of that interconnected focus and not limiting yourself to one area, how did you first hear about the carbon pipelines being proposed in Iowa? And what were some of the initial thoughts that you had?

JC: I first heard about the pipelines a couple of years ago. We’ve been working closely with Great Plains Action Society since we started our organization, they are an amazing Indigenous led organizing group here in Iowa. We’ve done a lot of work with them fighting for racial justice, fighting for the liberation of Black folks and for Indigenous folks. I think I first heard about the pipelines from Sikowis (Christine), they started to do some informational events. I know they were doing sharing a lot of stuff on social media, and having like some virtual town hall type of events where they're explaining what was going on with the pipelines. And I know folks like Sikowis and some other organizers here in Iowa who have been engaged in pipeline fights in the past, you know, with the Dakota Access Pipeline. It's something that I'm aware of, and opposing pipelines is something that I think is super important. Like I've known folks who, a couple years ago, were driving up to Minnesota for the Stop Line 3 protests. And when I heard that they're trying to build pipelines through Iowa, I was immediately concerned and immediately wanting to be involved in taking action against these pipelines and trying to stop that from happening.

AC: And you mentioned how Indigenous groups have really taken the lead opposing pipelines in the past, in this case, the opposition to Summit's project from primarily white landowners has really dominated media coverage so far. Why do you think that that is?

“The argument is that these private companies like Summit should not be able to use eminent domain to take people's land and then use that for private purposes to make profit for their companies, which is an argument I, of course, agree with. That's not what eminent domain should ever be used for. I think eminent domain has obviously been abused throughout the history of this country, and especially to the detriment of Black folks, when we think of the city of Des Moines and cities all across the country.”

JC: The framing around the pipelines has definitely been focused on white land landowners, like you said, and it's been this argument over eminent domain, which has been the main argument used against the pipelines. The argument is that these private companies like Summit should not be able to use eminent domain to take people's land and then use that for private purposes to make profit for their companies, which is an argument I, of course, agree with. That's not what eminent domain should ever be used for. I think eminent domain has obviously been abused throughout the history of this country, and especially to the detriment of Black folks, when we think of the city of Des Moines and cities all across the country. Right here in Des Moines, they used eminent domain to take Black folks’ homes away from them. And there was an entire Black community here on Center Street. I had family who lived there, grandparents who lived there, whose homes were taken away using eminent domain, and they were bulldozed so that they could build a freeway through it. I'm definitely sympathetic and understanding to the argument against eminent domain abuse, I think it's awful. It's a strong argument to make, I think we see that as the main argument, because we are in Iowa, over 90 percent white. And the areas where they're trying to build these pipelines do go through farmland in rural Iowa, where white folks own land, and they don't want to see that land get taken away. We're a deep red Republican state at this point, fully controlled by right wingers. If we want to actually have some sort of political wins, the arguments do need to be framed in a way that actually hits home and actually is impactful for folks who are making decisions. I see that as a reason why eminent domain has been such a focus in this fight and why white landowners have been prioritized so much in this fight.

But I think it's also a problem, because white landowners are not the only people who will be affected by these pipelines. In fact, Black folks, migrant folks in Iowa, Indigenous folks, they're the ones who are really going to face the brunt of it. They are facing the brunt currently of the ongoing climate crisis that we're facing. And it's only going to continue to get worse, especially with projects like these pipelines. And so, it's really important. I think that frontline communities, Black communities, Brown communities, Indigenous communities are loud and have a voice in this fight, and are acknowledged as being stakeholders, and people who really matter and whose voices are really important when it comes to the impact that these pipelines will have in the state.

AC: I've heard a lot from the white landowners who just cannot believe that eminent domain could be used in this way. And I think most of their cases, they're completely unaware of how it's been abused historically. You mentioned your own family, how it's been used to take land from Black and Brown communities across the US. I interviewed a member of the Winnebago tribe when we were working on the report, and she said something that's really stayed with me. The fear is not if pipelines will rupture, but when. And the impacts of a carbon pipeline rupture are catastrophic, as we saw in Mississippi, could you just talk a little bit about what happened in that case and how it relates to environmental racism?

JC: I think that quote is spot on. And I think what happened in Mississippi is something that I always try to bring up whenever discussing the dangers of these pipelines here in Iowa and really like trying to get folks to wrap their heads around how harmful this really will be. Because yeah, what happened in Mississippi is absolutely awful and horrifying. If you read accounts of folks on the ground experiencing the aftermath of what was a rupture and explosion of the CO2 pipeline in Satartia, Mississippi, that the pipeline ruptured and toxic CO2 gas spilled out of the pipeline and into the community. This is a community that was I think, over 40 percent Black. Folks not aware, right, when they have this, this CO2 gas that's just leaking out into the atmosphere into your community, they don't smell it. They don't taste it. I saw reports of how it was impacting people's vehicles, people trying to drive out of the situation and cars would start or just cut off completely, because they don't have oxygen in the air. And people passing out, right. I know, many, like dozens of people were sent to the hospital, many people were left permanently disabled. I think from reports I read, folks say that it's honestly a miracle that no one died, right. And this was 2020 that this happened, this is very recent. And this is the exact same infrastructure, the exact same technology that they want to build throughout Iowa. And we see that it's not safe, it's proven to be disastrous, in fact, it's untested technology. And they want to build three of these pipelines through Iowa, it's not just something Summit wants to build, Wolf wants to build one, Navigator wants to build one, they want to have three of these CO2 pipelines running through our state, running through communities.

They want to run a pipeline, right through Fort Dodge — in the flats of Fort Dodge, which historically has a large Black population, a low-income Black population. And we know that these companies like Summit, and these other pipeline corporations do not care about the communities that they're running these pipelines through, they don't care about the health impacts that these will have, they don't care about when these pipelines do rupture, you know, the devastating impacts that it will have on community members here in Iowa. They just care about their profits. I think, yeah, it's really important to continue to lift up what happened and talk about what happened in Mississippi as a warning to folks like this will happen here in Iowa, if we allow these corporations to continue with their plans to build these pipelines. We will have a situation like in 2020, what happened in Mississippi, and there will be people who are left permanently disabled or could die because of it.

AC: I remember that one of the emergency response directors said something about if the wind had shifted even slightly it could have led to even more of a disaster in Mississippi. And, just taking that risk again just seems incredibly irresponsible. Then you mentioned Fort Dodge as a community that will be near pipeline route and some other Black and Brown communities that will be near these routes. Because they'd be in danger, especially in the case of a rupture, are you aware of any consultation that's been done to inform these communities about the risks of the pipeline? To try to educate them about the project or get their input?

JC: No, I have not heard of intentional outreach being done to these frontline communities who will be impacted from the pipelines. I've heard a lot of outreach being done with white landowners, right, who are concerned about eminent domain abuse. They have a lot of town halls and a lot of informational sessions, where white landowners are specifically catered to. And, you know I've been told that white landowners are told they're the only ones allowed to talk at the meetings, like their voices are the only ones that matter in this conversation, which we know is not true. I think that that consultation is not happening but it needs to be happening. I think, you know, I do see that effort being taken by community organizations, right people on the ground who actually do care about these communities, you know, folks like Great Plains Action Society and other organizing groups who have been intentional about setting up community meetings. I know there's plans to drive around Iowa and have Town Hall style meetings with some of these frontline groups. None of that work is being done right now by Summit or by the power players involved in this, they don't care. Like we said, their main focus is on the white landowners.

And when we talk about Fort Dodge, and in the flats, you know, like I said, it's a Black low-income area where these pipelines will run right through. In Fort Dodge, there's, you know, a large prison, one of the largest prisons in the state is located in Fort Dodge. And what really concerns me when we talk about the possibility of a rupture of a pipeline. I have friends who are incarcerated in Fort Dodge prison, who I communicate with, I was the one who let them know about these pipelines and the fact that they might build these pipelines in Fort Dodge. They had not heard about them at all. And they started sharing information throughout the prison and letting folks know about this. A ton of people in there are concerned about this, and they have not received any information. I really am worried, because if we look at what happened in Mississippi, and if that were to happen in Fort Dodge, right, a CO2 pipeline rupturing, and this toxic gas being let out into the community, and that gets into Fort Dodge prison — we know that the correctional officers, and all the staff in prison, they can leave, they can get out of that that environment, and they can get to fresh air and somewhere where they're able to breathe. But the folks who are incarcerated, I can guarantee you are not going to be allowed to leave, they're going to be stuck in those cells and could suffocate. That's something that really worries me a lot about the possibility of these pipelines being built near Fort Dodge.

AC: That's the first I've heard of that risk. And as you said, it's really unimaginable what the impact there would be and really inexcusable that these communities have just been completely left out of any kind of planning, much less any sort of free, prior and informed consent that you would expect for a larger infrastructure pipeline like this

JC: 100 percent. We talked about environmental racism. And I think a lot of folks forget that incarcerated populations in these communities are on the frontlines and will be the worst impacted. When you look at what happened with Hurricane Katrina, in New Orleans, and what happened to incarcerated folks there, they were left in a flooded prison. While everyone else you know, got out of there. And so, you know, we've seen that happen throughout history, when these awful environmental disasters take place. It is incarcerated folks, poor Black folks, poor migrant folks, Indigenous folks who face the real brunt of it, and who are left behind in most circumstances.

AC: That's what we're really trying to get more attention to and just make more people aware of that fact, because it's really been overlooked in this case. So, to conclude, the DMBLM has really joined together with a broad coalition to oppose these projects. You mentioned, alongside GPAS and others. What about this struggle gives you hope that despite the political connections, the wealthy investors behind Summit their plans can still be stopped?

JC: Yeah, it's stuff like you said, the wealthy investors, we know that the political corruption is very deep. When it comes to these pipeline projects. If folks look at the Oakland Institute report and some of these other reports that have been released, you can literally draw a whole visual map of all the political corruption and all the players involved in how they're all connected and getting money from one another. It really can be hard, I think, to be hopeful and think that we're going to be able to stop this plan when all the powers that be in the state are fully invested in it. The fact that opposing the pipeline is a nonpartisan fight. Like we've already talked about white landowners, a lot of right wingers, a lot of Trump supporters and then on the other side, there's black abolitionists who are fighting for the same — to stop the pipelines. So, I think that that can provide some hope, knowing that we can have a broader coalition that will probably not agree on most issues, but can come together, hopefully to try to stop the pipelines.

But I know this wasn't your question, but I get discouraged to knowing that the fight to build these pipelines is also across party lines. You know, this is not just Republican supported. Yes, Kim Reynolds and her IUB that she appointed and Terry Branstad and the rest of them are all Republicans. But at the same time, there are many Democrats who support this plan. The AFL CIO of the labor union here in Iowa came out in support of the plan, because they think it's going to give them some good jobs to build the pipeline. We confronted one of the attorneys who is representing Summit, in this case, and he is a high donor for the Democratic Party. He's a liberal, right? He's a big Joe Biden supporter, he tried to tell us how could this plan be bad if Joe Biden's EPA approved it? So, that can be tough, knowing that there are so many Democrats that think that this is a good plan. They're either drinking the Kool Aid of the greenwashing, thinking that this actually is good for the environment, and this will help stop emissions or whatever else. And then there are others who don't care, because they also are just invested in padding their pockets and making profit. So that can be tough. But I think the folks who are opposed to the pipeline definitely out number the folks who support the pipeline. The folks who support the pipeline might have more money than us, and they might be in more positions of power than us. But last I saw was 80 percent of Iowans are against using eminent domain to build these pipelines, which is the only way they're going to get built really. The fact that we have, you know, Republican legislators introducing legislation and trying to stop this, you know, can provide some sort of hope, I guess. But really just the organizing and the folks who were involved on the ground, some of these frontline communities like we're talking about the amazing work that GPAS has been continuing to do. And some of these other folks, you just across the state who are so dedicated to showing up and continuing to fight against these pipelines. I think we will be able to stop these pipelines. I do think that is that is possible, and I think we can do it.

AC: Thank you so much Jalen for joining us today. For listeners who want to watch the full testimony that Jalen gave to the IUB as well as the report delivered to Summit’s lawyer — which I recommend you take a look at. Those are available on the Oakland Institute social media as well. Our final guest of the day is from the Iowa Migrant Movement for Justice, Alejandro Murgia-Ortiz is going to now share some of the concerns that migrant farmers would have with these projects as well as some broader issues that they face in Iowa and as they relate to environmental racism.

Alejandro Murgia-Ortiz (AM): My name is Alejandra Murgia-Ortiz. I'm a community organizer with Iowa Migrant Movement for Justice. A huge part of what we do is immigration, legal services. We have DOJ accredited reps and lawyers on staff, who were a part of those two organizations, and I was hired on in 2020 to kind of have an actual organizer working on the various issues. You know, in particular at the time, this was peak early pandemic, when I got largely involved with some of the issues we were hearing in meatpacking. So, the worker stuff, particularly meat packing, and since then and in many other fields is much of what I do — communicate with workers but also advocacy, in a broader sense when it comes to immigration advocacy at the local, state and federal level.

AC: There's been so much media coverage on opposition to this project from landowners, primarily white landowners who would be impacted by the pipeline. Have you heard any concerns from farm workers about this project once they've kind of learned about what it would be and the risks they would have?

AM: I would say at this point we're doing that outreach to educate them. We're still at the education stage. But we don't have an organized workforce. When it comes to these spaces, a lot of these workers are temporary. When you have some of the conversations, it's not a priority for understandable reasons. You know, whether it's workplace issues, like the pandemic, and the many folks in meat packing were dying, you know, of course, folks know that when there's issues and, you know, they want something to happen. But at the end of the day, the most important thing is being able to bring money back home, especially if you don't have status, it is hard to take risks. I mean, you're not able to risk as much because it means so much more to risk. Their health, the health of family, is incredibly important. But I think, largely because that work hasn't been happening. You know, we're really just at the beginning stages, making sure that this information is available for folks.

AC: For context could you describe some of the current conditions that migrant farmworkers face in Iowa?

“When we're talking about farmworkers, this is an industry that not only is there not much protection for workers, from PPE to worker’s rights. Just in general they are often very isolated from much of the rest of the state, and from the resources that exist in some of the major cities.”

AM: When we're talking about farmworkers, this is an industry that not only is there not much protection for workers, from PPE to worker’s rights. Just in general they are often very isolated from much of the rest of the state, and from the resources that exist in some of the major cities. It's even difficult for us to reach some of the workers out there. But what we know these workers are already in dangerous conditions, overworked and excluded from overtime pay in many of these industries. So already they are in very vulnerable situations, and very dangerous situations, where the environmental impacts of not only this but many ways that we're destroying the ecosystem here in Iowa are impacting them directly. They are on the frontlines of these very dangerous working conditions. This will only get worse when we introduce these new risks that seem to be very interconnected with these industries that very specifically hire migrant workers.

AC: That's very helpful to hear more about the current conditions they face, because if these pipelines are built, there's all this necessary training and protective equipment that you would need to respond to a disaster. And you know, you were mentioning, not even receiving PPE, it's very unlikely they would be put in a position where they'd be safe in the event of a pipeline rupture?

AM: They would probably be the last to hear about it.

AC: Right. In addition to risks while working, are you aware of risk for farmworkers in their own communities, given the pipeline routes? Are there any known cities or towns, you mentioned some meat packing towns that have a high proportion of migrant farmworkers near proposed pipeline routes?

AM: As we're still learning and we also know that the route can change, and that could mean changing to impact even more communities of color. But right now, we're seeing Storm Lake, my hometown of Sioux City, Denison, those are all huge communities where migrant workers are, and seem to be in near pipeline routes. It's going to definitely be impacting communities in their own backyards. We know that the state isn't going to prioritize those communities. It's going to end up falling on to the community itself to be able to come together. Again, we'll be the last to be communicated with, and especially in an effective manner that is culturally competent.

AC: To your knowledge, there's been no consultation so far from Summit or the other pipeline companies with farmworker communities?

AM: I cannot imagine, I have not heard of any. And there's no, I can't say for sure, but I am fairly confident that there hasn't been. You know, maybe with their employers? But that doesn't mean that that's going to make it to the workers.

AC: Does this environmental racism surprise you? Or is this something that's been experienced previously?

AM: No, I mean, this is something that we experience on daily basis. And that's largely because those communication mechanisms, that the cultural education for decision makers just isn't there in the state. So yeah, I mean, that not only in terms of how we communicate, or even if we communicate these things to communities, but also just like, knowing these things are going to impact communities of color. And that's just something that we see, not only environmental, but just racism as a whole, and that manifests in environmental racism. We definitely, definitely see that.

AC: And to conclude, you've spoken about this coalition opposing the project, what about the efforts so far gives you hope that it can be stopped despite the odds?

AM: I think that in the past, the intersections of migrant justice and climate justice have largely been ignored in these movements. And this a really important piece. And by putting that piece together, I mean, I think it's only a positive in terms of like, the strength that we can have, if we continue this work, and really bring folks into that. I think that's incredibly important, you know, not just in terms of like pushing back against the pipeline, and getting people aware of what that's going to mean for our communities. But also in the long term, when it comes to climate justice, and the future of agriculture, especially given how interconnected Big Ag is, and these large companies with climate migration and climate displacement. In general, you know, the workforce that these companies have there is a very direct connection that is often ignored. Making that connection, I think it's going to be only a positive.

AC: Thank you Alejandro. Now, the report the The Great Carbon Boondoggle goes more in depth on a lot that we've heard today and is available on the Oakland Institute website, be sure to sign up to the reporter newsletter, and follow us on social media to see how this develops. The timeline for the IUB to decide on eminent domain is unclear at this time, but we will be providing updates as it develops and continue to work with communities on the ground to resist these dangerous false climate solutions.

Thank you as always for listening — until next time.