The World Bank's Fetish For Ranking: The Case Of Doing Business Rank For Chile

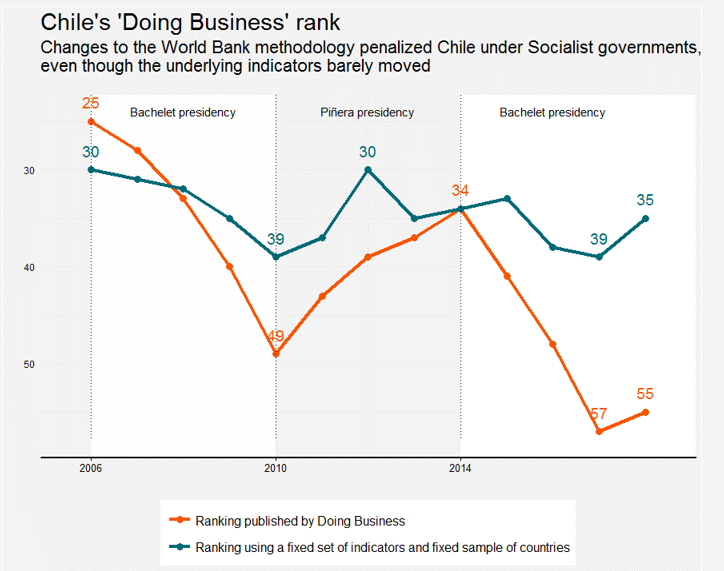

On January 12, 2018, World Bank Chief Economist Paul Romer revealed that the Bank’s Doing Business Ranking may have been deliberately skewed and politically manipulated, disfavoring Chile’s ranking under its outgoing socialist president, Michelle Bachelet. Following these revelations, he resigned on January 24.

Romer uncovered how ‘methodological changes’ in the Bank’s Ranking system resulted in an abrupt drop in Chile's scores during President Bachelet’s first (2006-2010) and second term (2014-2018), while the country’s score rose sharply under the presidency of conservative billionaire Sebastián Piñera (2010-2014). These sharp fluctuations were primarily a result of methodological changes on a group of indicators, and not because of actual reforms in laws or policies.

What Does Doing Business Ranking Measure and How Does It Affect Countries? The Case Of Chile

Since 2002, the World Bank has scored countries — through the Doing Business ranking — according to how well they are improving the “ease of doing business”. In order to improve their ranking, governments must carry out business-friendly reforms such as reducing corporate tax, labor and environmental regulations. The World Bank claims that its ranking has resulted in over 3,188 regulatory reforms around the world since 2006. During this period Chile carried out only eight reforms, seven of which were qualified by the Bank as making it easier to do business and one which did not — President Michelle Bachelet’s latest tax reform approved by Congress in 2014. This tax reform — that raised corporate taxes and closed some tax exemptions — along with a promise of a new constitution and free schooling constituted an agenda that many voters hoped would rid Chile of its neo-liberal legacy inherited from Augusto Pinochet’s military dictatorship from 1973 to 1990.

Chile: Friedman’s Own Neo-liberal Experiment

Chile was one of the first countries in the world that adopted a neo-liberal market economy. The reforms implemented after 1973 were enforced by a military dictatorship that ruled Chile between 1973 and 1990. Although the dictatorship is estimated to have left 3,000 dead or missing, tortured tens of thousands of prisoners, and drove an estimated 200,000 Chileans into exile, it was hailed by the economist Milton Friedman as an ‘economic miracle’.

Chilean neo-liberalism was early on promoted by a technocratic elite disciple of Friedman and the Chicago school of economics, known as the Chicago Boys. It was Friedman himself who convinced General Pinochet to adopt a set of aggressive economic reforms including lowering public spending by 20 percent, discharging 30 percent of public employees, increasing the value-added tax. Most importantly, Friedman advised Pinochet that his students should enter his government. Under the sway of a pro-market doctrine, they created Chile’s current private health system, the first private and individual capitalization pension system, and an inequitable and expensive higher education system.

The Chilean Miracle?

The supporters of neo-liberal reforms until today highlight the positive effects the reforms have had on macro-economic indicators, such as Gross Domestic Product (GDP), investment, savings and low inflation rates. But they fail to mention the devastating effects of the deregulation of the market on people’s quality of life, especially for the poorest. The percentage of Chilean population living in poverty rose from 17 percent in 1969 to 45 percent in 1985, wages decreased by 8 percent and unemployment rose to 20.3% by 1982. Between 1970, the richest 10 percent of the population saw their share in the national income rise from 36.5 percent in 1980 to 46.8 percent by 1989 (the bottom 50 percent saw their share fall from 20.4 to 16.8 percent). Since 1990, the generation of employment has also failed to keep pace with economic growth. Empirically, little can be seen of the so called “Chilean Miracle”.

The Threat Of Structural Reforms?

This situation had never been structurally challenged by a sitting President in Chile; Michelle Bachelet was to become the first, through the implementation of tax, labor and education reforms that aimed at the easing of social inequality. And although the effects of Bachelet’s reforms are not yet assessable, her public policy choices were attacked with one argument — they would hinder growth and investment.

While the GDP has increased less during Pres. Bachelet’s second term than it did during her first term, the problem with assessing all reforms only in light of how they hinder or increase investment and economic growth, ignores that these indicators do not (necessarily) lead to improvements in quality of life. Chile’s recent history demonstrates that.

The World Bank’s Doing Business ranking provides arguments to dismiss potentially positive effects of structural reforms, such as those implemented by Bachelet. It is worth mentioning that the World Bank itself has estimated that Bachelet’s tax reform will have a positive impact on income distribution and tax equality. Despite this, the incoming President Piñera has already promised to lower taxes for big businesses and other measures that will benefit the wealthiest who in Chile already control 72 percent of the national wealth. The aim: increase GDP and encourage foreign investment.

Developing countries, such as Chile, eager to improve their position in international rankings carry out public policy reforms that are often (only) assessed by how much it will enhance the nation’s relative position — developing almost a fetish for it. The problem is that the countries and international institutions are deliberately ignoring what these rankings aim to accomplish. The World Bank’s Doing Business ranking encourages a race to the bottom between countries to deregulate, and not a race aimed at improvement of quality of life for the people and not even an increase in economic growth and investment.

This is why the Our Land Our Business campaign demands the end of the Bank’s Doing Business rankings. Over 280 organizations, including NGOs, unions, farmers, and consumer groups from over 80 countries have joined this call so far. The revelations by the Bank’s former Chief Economist yet once again demonstrate that business rankings are not there to help the poor but serve a political agenda that benefits the most powerful. This makes it more important than ever to end the World Bank’s Doing Business ranking.

Read the reports:

Willful Blindness: How the World Bank’s Doing Business (DB) Rankings Impoverish Smallholder Farmers

The Unholy Alliance, Five Western Donors Shape a Pro-Corporate Agenda for African Agriculture

New Name, Same Game: World Bank's Enabling the Business of Agriculture

Read the statement signed by over 280 organizations

For more information, visit the campaign website (English, French, Spanish)